From youtube:

From Luft '46:

In June 1935 and February 1936, Dr. Eugen Sänger published articles in the Austrian aviation publication Flug on rocket-powered aircraft. This led to his being asked by the German High Command to build a secret aerospace research institute in Trauen to research and build his "Silverbird", a manned, winged vehicle that could reach orbit. Dr. Sänger had been working on this concept for several years, and in fact he had began developing liquid-fuel rocket engines. From 1930 to 1935, he had perfected (through countless static tests) a 'regeneratively cooled' liquid-fueled rocket engine that was cooled by its own fuel, which circulated around the combustion chamber. This engine produced an astounding 3048 meters/second (10000 feet/second) exhaust velocity, as compared to the later V-2 rocket's 2000 meters/second (6560 feet/second). Dr. Sänger, along with his staff, continued work at Trauen on the "Silverbird" under the Amerika Bomber program.

In June 1935 and February 1936, Dr. Eugen Sänger published articles in the Austrian aviation publication Flug on rocket-powered aircraft. This led to his being asked by the German High Command to build a secret aerospace research institute in Trauen to research and build his "Silverbird", a manned, winged vehicle that could reach orbit. Dr. Sänger had been working on this concept for several years, and in fact he had began developing liquid-fuel rocket engines. From 1930 to 1935, he had perfected (through countless static tests) a 'regeneratively cooled' liquid-fueled rocket engine that was cooled by its own fuel, which circulated around the combustion chamber. This engine produced an astounding 3048 meters/second (10000 feet/second) exhaust velocity, as compared to the later V-2 rocket's 2000 meters/second (6560 feet/second). Dr. Sänger, along with his staff, continued work at Trauen on the "Silverbird" under the Amerika Bomber program.

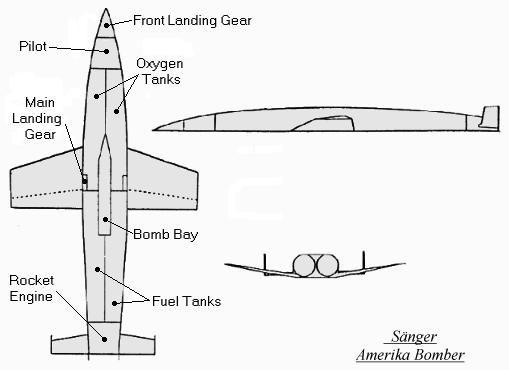

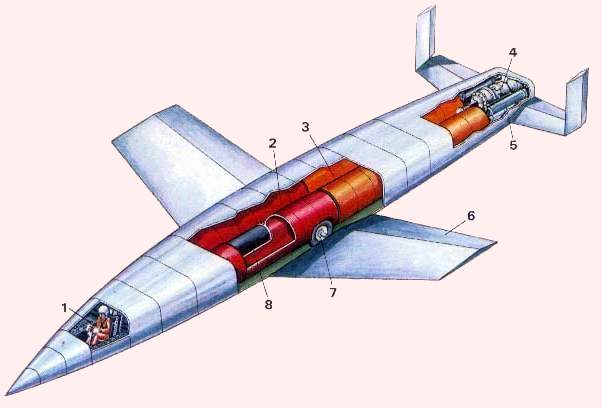

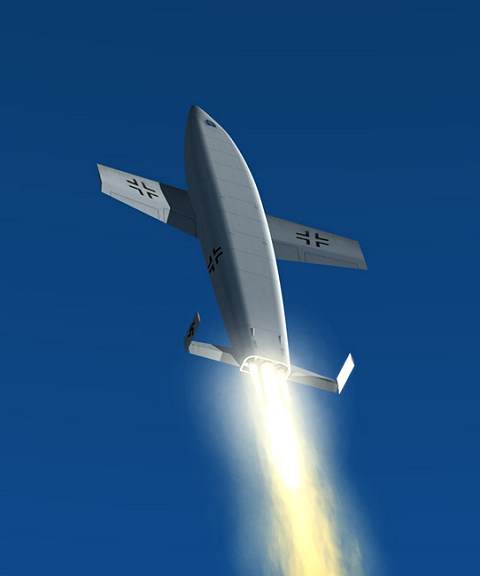

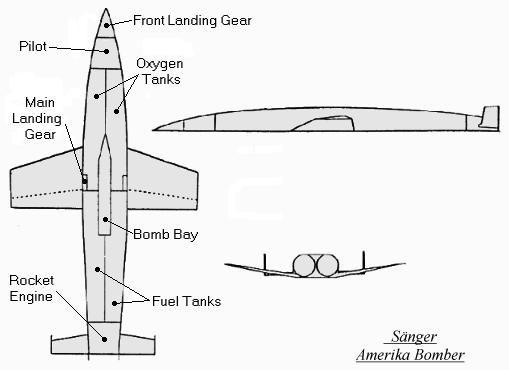

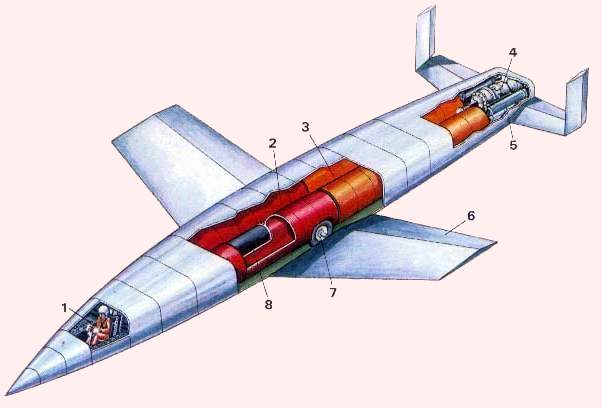

The Sänger Amerika Bomber (or Orbital Bomber, Antipodal Bomber or Atmosphere Skipper) was designed for supersonic, stratospheric flight (please see diagram below). The fuselage was flattened, which helped create lift and the wings were short and wedge shaped. There was a horizontal tail surface located at the extreme aft end of the fuselage, which had a small fin on each end. The fuel was carried in two large tanks, one on each side of the fuselage, running from the wings aft. Oxygen tanks were located one on each side of the fuselage, located forward of the wings. There was a huge rocket engine of 100 tons thrust mounted in the fuselage rear, and was flanked by two auxiliary rocket engines. The pilot sat in a pressurized cockpit in the forward fuselage, and a tricycle undercarriage was fitted for a gliding landing. A central bomb bay held one 3629 kg (8000 lb) free-falling bomb, and no defensive armament was fitted. The empty weight was to be approximately 9979 kg (22000 lbs).

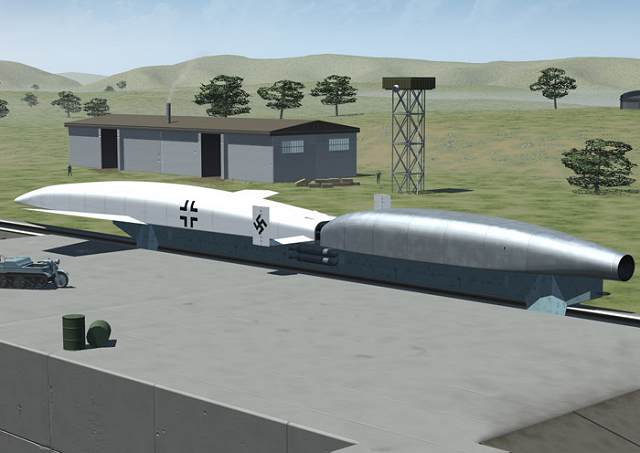

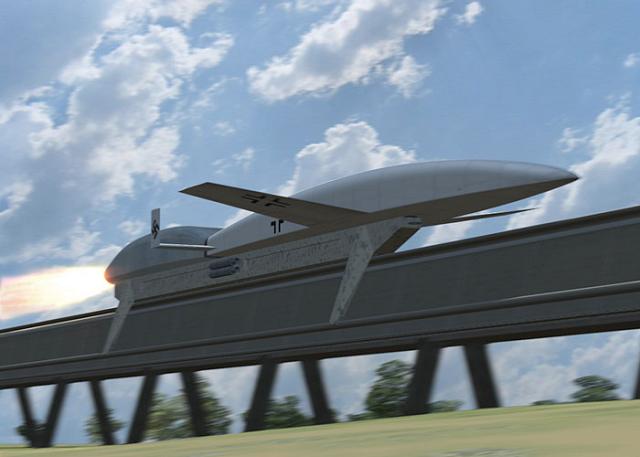

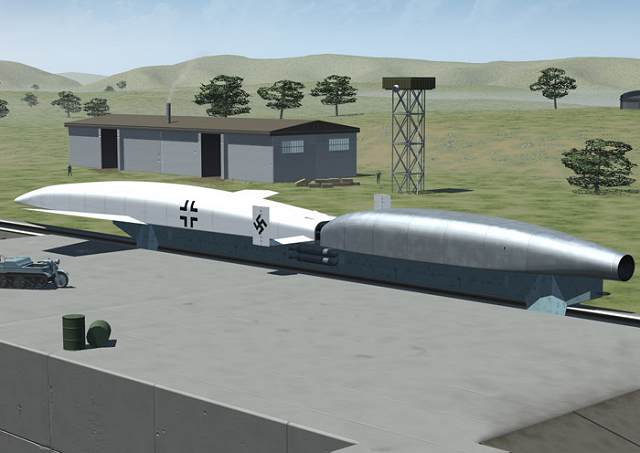

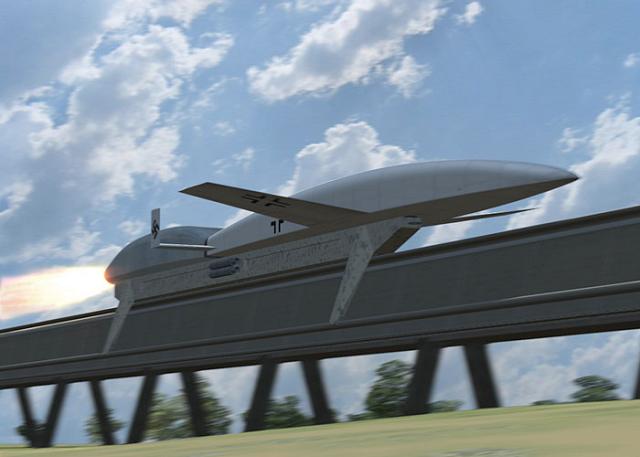

An interesting flight profile was envisioned for the "Silverbird". It was to be propelled down a 3 km (1.9 mile) long monorail track by a rocket-powered sled that developed a 600 ton thrust for 11 seconds (please see diagram below). After taking off at a 30 degree angle and reaching an altitude of 1.5 km (5100'), a speed of 1850 km/h (1149 mph) would be reached. At this point, the main rocket engine would be fired for 8 minutes and burn 90 tons of fuel to propel the "Silverbird" to a maximum speed of 22100 km/h (13724 mph) and an altitude of over 145 km (90 miles), although some sources list the maximum altitude reached as 280 km (174 miles). As the aircraft accelerated and descended under the pull of gravity, it would then hit the denser air at about 40 km (25 miles) and 'skip' back up as a stone does when skipped along water (please see drawing below). This also had the added benefit of cooling the aircraft after the intense frictional heating encountered when the denser air was reached. The skips would gradually be decreased until the aircraft would glide back to a normal landing using its conventional tricycle landing gear, after covering approximately 23500 km (14594 miles).

The final test facilities for full-scale rocket engine tests were being built when Russia was invaded in June 1941. All futuristic programs were canceled due to the need to concentrate on proven designs. Dr. Sänger went on to work on ramjet designs for the DFS (German Research Institute for Gliding), and helped to design the Skoda-Kauba Sk P.14. Although the Luftwaffe did its best to stop Dr. Sänger from publishing his research results, a few copies went unaccounted for and made their way to other countries. After the war, he was asked to work (along with mathematician Irene Bredt) for the French Air Ministry, where in a bizarre plot, he was almost kidnapped by Stalin, who recognized the value of the Amerika Bomber.

![[silverbird-big.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhprYPzArguNV1PHPI0WVCUbyvF4oJEqIeuptZEKiJiSc-78auEMn84HhpIAJLXpS2Tl2R3lStcqHiZ2EQ15-lJO2fgAMGuQowmdfBXYl4JVIC_pgYg_WswF02R5SBl1J20Xggvep3gI9c/s640/silverbird-big.jpg)

From Wikipedia:

Amerika Bomber

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Amerika Bomber project was an initiative of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium, the Nazi Germany Air Ministry, to obtain a long-range strategic bomber for the Luftwaffe that would be capable of striking the continental United States from Germany, a range of about 5,800 km (c.3,600 mi.). Though the concept was raised as early as 1938, plans were not submitted to Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring until 1942. Various proposals were put forward, including using it to deliver an atomic bomb, but they were all eventually abandoned as too expensive.

Background

According to Spandau: The Secret Diaries, Hitler was fascinated with the idea of New York City in flames. In 1937, Willy Messerschmitt hoped to win a lucrative contract by showing Hitler a prototype of the Messerschmitt Me 264 that was being designed to reach North America from Europe.[1] On July 8, 1938, barely two years after the death of Germany's main strategic bombing advocate, Generalleutnant Walter Wever, the Luftwaffe's commander-in-chief Hermann Göring, gave a speech saying, "I completely lack the bombers capable of round-trip flights to New York with a 4.5-tonne bomb load. I would be extremely happy to possess such a bomber which would at last stuff the mouth of arrogance across the sea."[2] Canadian historian Holger H. Herwig[3] claims the plan started as a result of discussions by Hitler in November 1940 and May 1941 when he stated his need to “deploy long-range bombers against American cities from the Azores.” Due to their location, he thought the Portuguese Azores islands were Germany's “only possibility of carrying out aerial attacks from a land base against the United States.”[2] At the time, Portuguese dictator Salazar had allowed German U-boats and navy ships to refuel there, but from 1943 onwards, he leased bases in the Azores to the British, allowing the Allies to provide aerial coverage in the middle of the Atlantic.

Requests for designs, at various stages during the war, were made to the major German aircraft manufacturers (Messerschmitt, Junkers, Heinkel, Focke-Wulf and the Horten Brothers) early in World War II, coinciding with the passage of the Destroyers for Bases Agreement between the United States and the United Kingdom in September 1940.

The plan

The Amerika Bomber Project plan was completed on April 27, 1942 and submitted to Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring on May 12, 1942. The 33 page long plan was discovered in Potsdam by Olaf Groehler, a German historian. Ten copies of the plan were made, with six going to different Luftwaffe offices and four held in reserve. The plan specifically mentions using the Azores as a transit airfield to reach the United States. If utilized, the Heinkel He 277, Junkers Ju 290, and the Messerschmitt Me 264 could reach American targets with a 3 ton, 5 ton, and 6.5 ton payload respectively.[2] Although it is apparent that the plan itself deals only with an attack on American soil, it is possible the Nazis saw other, interrelated strategic purposes for the Amerika Bomber project. According to military historian James P. Duffy, Hitler "saw in the Azores the ... possibility for carrying out aerial attacks from a land base against the United States ... [which in turn would] force it to build up a large antiaircraft defense."[2] The anticipated result would have been to force the United States to use more of its antiaircraft capabilities - i.e. guns and fighter planes - for its own defense rather than for that of Great Britain, thereby allowing the Luftwaffe to attack the latter country with less resistance.

Potential targets

Included in the plan was a list of 21 targets of military importance. Of these, 19 were located in the United States and the remaining two in Vancouver, Canada and the southern tip of Greenland. Nearly all were companies that manufactured parts for aircraft, so the goal for Nazis was likely to cripple American production of aircraft. The 19 targets are listed below by company and location.[2]

Aluminum Corp. of America in Alcoa, Tennessee

Aluminum Corp. of America in Massena, New York

Aluminum Corp. of America in Badin, North Carolina

Wright Aeronautical Corp. in Paterson, New Jersey

Pratt & Whitney Aircraft in East Hartford, Connecticut

Allison Division of G.M. in Indianapolis, Indiana

Wright Aeronautical Corp. in Cincinnati, Ohio

Hamilton Standard Corp. in E. Hartford, Connecticut

Hamilton Standard Corp. in Pawcatuck, Connecticut

Curtiss Wright Corp. in Beaver, Pennsylvania

Curtiss Wright Corp. in Caldwell, New Jersey

Sperry Gyroscope in Brooklyn, New York

Cryolite Refinery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

American Car & Foundry in Berwick, Pennsylvania

Colt Manufacturing in Hartford, Connecticut

Chrysler Corp. in Detroit, Michigan

Allis-Chalmers in La Porte, Indiana

Corning Glass Works in Corning, New York

Bausch & Lomb in Rochester, New York

Conventional bombers

The most promising proposals were based on conventional principles of aircraft design and would have yielded aircraft very similar in configuration and capability to the Allied heavy bombers of the day. These included the Messerschmitt Me 264 (an all-new design), the Focke-Wulf Fw 300 (based on the existing Fw 200), Focke Wulf Ta 400, and the Junkers Ju 390 (based on the Ju 290), as well as the Heinkel He 277, which from its design's ongoing development through 1943, eventually ended up as worthy to compete for the "Amerika Bomber" role. Prototypes of the Me 264 were built, but it was the Ju 390 that was selected for production. Only three prototypes each, of both the Me 264 and Ju 390 designs, were constructed before the programmes were abandoned. It has been claimed[citation needed] in a number of postwar World War II air combat subject books, that in early 1944 the second prototype of the Ju 390 made a trans-Atlantic flight to within 20 km (12 mi) of the northeast U.S. coast.

Huckepack Projekt (Piggyback Project)

One idea similar to Mistel-Gespann was to have a Heinkel He 177 bomber carry a Dornier Do 217, powered with an additional Lorin-Staustrahltriebwerk (Lorin-ramjet), as far as possible over the Atlantic before releasing it. For the Do-217 it would have been a one-way trip. The plane would be ditched off the east coast, and its crew would be picked up by a U-boat that was waiting nearby. When plans had advanced far enough, the lack of fuel and the loss of the base at Bordeaux prevented a test. The project was abandoned after the forced move to Istres increased the distance too much.

Atomic bomber

The controversial revisionist British historian David Irving stated that a method of bombing New York City was discussed at several Luftwaffe conferences in May and June 1942. One idea that received a lot of attention was the Huckepack Projekt (piggyback project). Initially Field-Marshal Erhard Milch vetoed the plan due to the small payload that would be delivered for such a massive project. However, on June 4, 1942, Erhard Milch and Albert Speer attended a lecture by Werner Heisenberg on atomic fission at the Harnack-Haus.[4] After the lecture, Speer asked Heisenberg if this research could design an atom bomb. Heisenberg replied that it could be done, but would take as long as two years. Speer then asked how large a bomb would need to be to destroy a city to which Heisenberg replied the size of a football.[2] Heisenberg requested funds, rare materials, and scientists be released from the army to continue their research. The Huckepack Projekt was brought up again at multiple joint conferences between the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. However, after a few weeks the plan was abandoned on August 21, 1942. Air Staff General Kreipe wrote in his diary that the German Navy could not supply a U-boat offshore of the United States to pick up the aircrew. The plan saw no further development, since the Kriegsmarine would not cooperate with the Luftwaffe.[2]

Flying wings

Other proposals were far more exotic jet- and rocket-powered designs, e.g. as a flying wing. The Horten brothers designed the Horten Ho XVIII,[5] a flying wing powered by six turbojets based on experiences with their existing Ho X design. The Arado company also suggested a six-jet flying wing design, the Arado E.555.[6]

Daimler-Benz Project C

Another proposal was the Daimler-Benz Project C. This was a huge carrier aircraft, carrying either five "Project E" aircraft or six "Project F" aircraft. The smaller aircraft had jet-engines and were designed to be kamikaze-airplanes.[7][8][9]

Winged rockets

Wind tunnel model of Eugen Sänger's Silbervogel

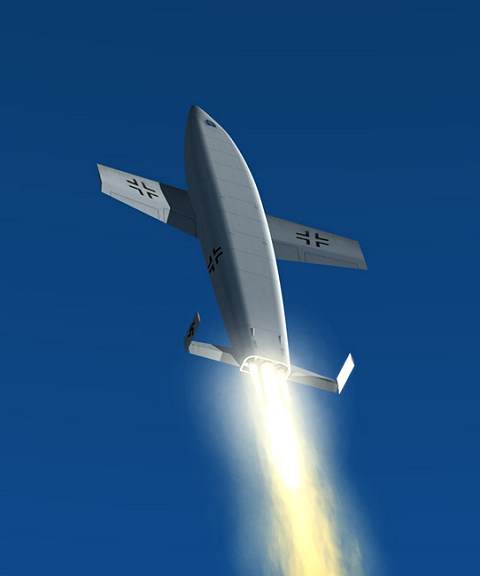

Other designs were rockets with wings. Perhaps the best-known of these today is Eugen Sänger's pre-war Silbervogel ("Silverbird") sub-orbital bomber. While the A4b rocket, winged version of the V-2 rocket and probably its successor A9 rocket were tested several times in late 1944/early 1945, the A9/A10 Amerika-Rakete, planned as a full 2-staged ICBM, remained a project.[10]

Feasibility

All of these projects were deemed too expensive and ambitious and were abandoned, although the British Air Ministry considered development of the Ho XVIII for an airliner after the war[citation needed], and the theoretical groundwork done on the Silbervogel would prove seminal to lifting body designs of the space age.

According to British Intelligence, a German prisoner of war was quoted saying that since the beginning of 1944, “…regular air travel between Germany and Japan established for the transport of high officials,” took place with the Messerschmitt Me 264.[11] The distance from Frankfurt, Germany to Tokyo, Japan is 9,160 km (5,691 mi) whereas the distance from New York City, New York to Paris, France is 5,840 km (3,628 mi) to put this in perspective. Although in the case of bombing New York City, that distance must be doubled to 11,680 km (7,256 mi) as the bomber will not be able to land as it did in Tokyo. The only German World War II aircraft built that had anything close to this specified range was the Messerschmitt Me 261 Adolfine, with a maximum range of 11,025 km (6,850 mi). Many engineering challenges would have to have been overcome for the bomber to be an effective weapon. Had Hitler spent more time and resources on this project, it may have had a chance of working. However, unless Germany developed an atomic bomb, which would have taken even more time and resources, it is unlikely this aircraft would have made a big impact on the outcome of the war.

Why the plan failed

Duffy believed that Nazi Germany had no central authority over the development and construction of advanced weaponry. Because of this, German scientists were forced to compete for resources that were already scarce due to the war. Hitler was often swayed to spend more time, money and resources on his “miracle weapons” or projects that were exciting and new, but less likely to be successful. As a result insufficient attention was given to the Amerika Bomber project. The project failed to come to fruition, not because the transatlantic bomber was not feasible, but because the Nazis were unable to manufacture enough parts to produce the aircraft. The Allied bombing was so intense near the end of the war it disrupted the German supply chain. Also, the German war machine was running very low on supplies, particularly fuel and kept what little was left for defense.[2]

References

1.^ Elke Frenzel Hitler's Unfulfilled Dream of a New York in Flames Der Spiegel 16 September 2010

2.^ a b c d e f g h Duffy, James P. Target America: "Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States". The Lyons Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1-59228-934-9.

3.^ http://hist.ucalgary.ca/faculty/herwig-holger-h

4.^ Rose, Paul; Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi atomic bomb project: a study in German culture By Paul Lawrence Rose Heisenberg and the Nazi atomic bomb project. ISBN 978-0-520-22926-6.

5.^ Horten XVIII, luft46.

6.^ Arado 555, luft46.

7.^ Project C, WW2 in color.

8.^ Project C, Above Top Secret

9.^ (GIFF) Project D, Something Awful.

10.^ http://www.luft46.com/misc/sanger.html Sänger page on luft46.com

11.^ Me 264 Forsyth, Robert. Messerschmitt Me 264 America Bomber: The Luftwaffe’s Lost Transatlantic Bomber. Ian Allen Publishing, 2006 ISBN 1-903223-65-2.

Further reading

Luftfahrt History Heft 4 - Messerschmitt Me 264 & Junkers Ju 390 *Atomziel New York - Geheime Großraketen- und Raumfahrtprojekte des Dritten Reichs

Griehl, Manfred and Dressel, Joachim. Heinkel He 177-277-274, Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury, England 1998. ISBN 1-85310-364-0.

Green, William. Warplanes of the Third Reich. London: Macdonald and Jane's Publishers Ltd., 1970. ISBN 0-356-02382-6.

Herwig, Dieter and Rode, Heinz. Luftwaffe Secret Projects - Strategic Bombers 1935-45. Midland Publishing Ltd., 2000. ISBN 1-85780-092-3.

Smith, J.R. and Kay, Anthony. German Aircraft of the Second World War. London: Putnam and Company, Ltd., 1972. ISBN 0-370-00024-2.

Duffy, James P. Target America: Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States. The Lyons Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1-59228-934-9.

Eugen Sänger

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Eugen Sänger

Born: 22 September 1905, Preßnitz

Died: 10 February 1964

Nationality: German

Work

Significant advance: lifting body and ramjet

Eugen Sänger (22 September 1905 - 10 February 1964) was an Austrian-German aerospace engineer best known for his contributions to lifting body and ramjet technology.

Early career

Sänger was born in the former mining town of Preßnitz (Přísečnice), Chomutov (flooded by the Preßnitz dam in 1974) in Bohemia, at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He studied civil engineering at the Technical Universities of Graz and Vienna. As a student, he came in contact with Hermann Oberth's book Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen ("By Rocket into Planetary Space"), which inspired him to change from studying civil engineering to aeronautics. He also joined Germany's amateur rocket movement, the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (VfR - "Society for Space Travel") which was centered on Oberth.

Sänger made rocket-powered flight the subject of his thesis, but it was rejected by the university as too fanciful. He was allowed to graduate when he submitted a far more mundane paper on the statics of wing trusses. Sänger would later publish his rejected thesis under the title Raketenflugtechnik ("Rocket Flight Engineering") in 1933. In 1935 and 1936, he published articles on rocket-powered flight for the Austrian journal Flug ("Flying.") These attracted the attention of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM, or "Reich Aviation Ministry") which saw Sänger's ideas as a potential way to accomplish the goal of building a bomber that could strike the United States from Germany (the Amerika Bomber project).

Sub-orbital bomber concept

Main article: Silbervogel

Sänger agreed to lead a rocket development team in the Lüneburger Heide region in 1936. He gradually conceived a rocket-powered sled that would launch a bomber with its own rocket engines that would climb to the fringe of space and then skip along the upper atmosphere - not actually entering orbit, but able to cover vast distances in a series of sub-orbital hops. This remarkable design was called the Silbervogel ("Silverbird") and would have relied on its fuselage creating lift (as a lifting body) to carry it along its sub-orbital path. Sänger was assisted in this design by mathematician Irene Bredt, whom he married. Sänger also designed the rocket motors that the space-plane would use, which would need to generate 1 meganewton (225,000 lbf) of thrust. In this design, he was one of the first to suggest using the rocket's fuel as a way of cooling the engine, by circulating it around the rocket nozzle before burning it in the engine.

By 1942, the Reich Air Ministry canceled this project along with other more ambitious and theoretical designs in favour of concentrating on proven technologies. Sänger was sent to work for the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug (DFS, or "German Gliding Research Institute"). There he did important work on ramjet technology until the end of World War II.

Postwar

After the war ended, Sänger worked for the French government and in 1949 founded the Fédération Astronautique. Whilst in France, he was the subject of a botched attempt by Soviet agents to win him over. Joseph Stalin had become intrigued by reports of the Silbervogel design and sent his son, Vasily, and scientist Grigori Tokaty to convince him to come to the Soviet Union, but they failed to do so. It has also been reported that Stalin instructed the NKVD to kidnap him.[1]

In 1951, he became the first President of the International Astronautical Federation.

By 1954, Sänger had returned to Germany and three years later was directing a jet propulsion research institute in Stuttgart. Between 1961 and 1963 he acted as a consultant for Junkers in designing a ramjet-powered space-plane that never left the drawing board. Sänger's other theoretical innovations during this period were proposing means of using photons for interplanetary and interstellar spacecraft propulsion, including the solar sail.

He died in Berlin. The Sänger's grave is located on the cemetery "Alter Friedhof" in Stuttgart-Vaihingen. His work on the Silbervogel would prove important to the X-15, X-20 Dyna-Soar, and ultimately Space Shuttle programs.

Honours

Elected Honorary Fellow of the British Interplanetary Society (B.I.S.) in 1949[2]

Notes

1.^ Wade, Mark. "Keldysh Bomber". Astronautix.com. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

2.^ "Dr Eugen Sänger". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society March 1950 vol 9 No.2. 1950.

References

Books and technical reports

Sänger, Eugen (1956). Zur Mechanik der Photonen-Strahlantriebe. München,: R. Oldenbourg. pp. 92.

Sänger, Eugen (1957). Zur Stahlungsphysik der Photonen-Strahlantriebe und Waffenstrahlen. München: R. Oldenbourg. pp. 173.

Sänger, Eugen (1933). Rocket Flight Engineering. (Washington, 1965): NASA Tech. Trans. F-223.

Sänger, Eugen; Irene Sänger-Bredt (August 1944). "A Rocket Drive For Long Range Bombers" (PDF). Astronautix.com. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

Saenger, Hartmut E and Szames, Alexandre D, From the Silverbird to Interstellar Voyages, IAC-03-IAA.2.4.a.07.

Sänger, Eugen; trans, Karl Frucht (1965). Space Flight: Countdown for the Future. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Duffy, James P. (2004). TARGET: AMERICA : Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96684-4.

Shayler, David J. (2005). Women in Space - Following Valentina. Springer. ISBN 1-85233-744-3.

Other

Westman, Juhani (2006). "Global Bounce". Retrieved 2008-01-17.

Wade, Mark. "Eugen Albert Saenger". Astronautix.com. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

From Wikipedia:

Silbervogel

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Sänger Silbervogel wind tunnel model

Silbervogel, German for silver bird, was a design for a rocket-powered sub-orbital bomber aircraft produced by Eugen Sänger and Irene Bredt in the late 1930s for The Third Reich/Nazi Germany. It is also known as the RaBo (Raketenbomber or "rocket bomber"). It was one of a number of designs considered for the Amerika Bomber mission. When Walter Dornberger attempted to create interest in military spaceplanes in the United States after World War II, he chose the more diplomatic term antipodal bomber.

Concept

The design was a significant one, as it incorporated new rocket technology, and the principle of the lifting body, forshadowing future development of winged spacecraft such as the X-20 Dyna-Soar of the 1960s and the Space Shuttle of the 1970s. In the end, it was considered too complex and expensive to produce. The design never went beyond mock up test.

The Silbervogel was intended to fly long distances in a series of short hops. The aircraft was to have begun its mission propelled along a 3 km (2 mi) long rail track by a large rocket-powered sled to about 1,930 km/h (1,200 mph). Once airborne, it was to fire its own rocket engine and continue to climb to an altitude of 145 km (90 mi), at which point it would be travelling at some 22,100 km/h (13,700 mph). It would then gradually descend into the stratosphere, where the increasing air density would generate lift against the flat underside of the aircraft, eventually causing it to "bounce" and gain altitude again, where this pattern would be repeated. Because of drag, each bounce would be shallower than the preceding one, but it was still calculated that the Silbervogel would be able to cross the Atlantic, deliver a 4,000 kg (8,800 lb) bomb to the continental US, and then continue its flight to a landing site somewhere in the Japanese held Pacific, a total journey of 19,000 to 24,000 km (12,000 to 15,000 mi).

Postwar analysis of the Silbervogel design involving a mathematical control analysis unearthed a computational error and it turned out that the heat flow during the initial re-entry would have been far higher than originally calculated by Sänger and Bredt; if the Silbervogel had been constructed according to their flawed calculations the craft would have been destroyed during re-entry. The problem could have been solved by augmenting the heat shield, but this would have reduced the craft's already small payload capacity.[1]

History

On 3 December 1941 Sänger sent his initial proposal for a suborbital glider to the Reich Air Ministry (RLM) as Geheime Kommandosache Nr. 4268/LXXX5. The 900-page proposal was regarded with disfavor at the RLM due to its size and complexity and was filed away.

Professor Walter Gregorii had Sänger rework his report and a greatly reduced version was submitted to the RLM in September 1944, as UM 3538. It was the first serious proposal for a vehicle which could carry a pilot and payload to the lower edge of space.

Two manned and one unmanned version were proposed: the Antipodenferngleiter (antipodal long-range glider) and the Interglobalferngleiter (intercontinental long-range glider). Both were to be launched from a rocket-powered sled. The two manned versions were identical except in payload. The Antipodenferngleiter was to be launched at a very steep angle (which would shorten the range) and after dropping its bomb load on New York City was to land at a Japanese base in the Pacific.[2]

Postwar

After the war ended, Sänger and Bredt worked for the French government[3] and in 1949 founded the Fédération Astronautique. Whilst in France, Sänger was the subject of a botched attempt by Soviet agents to win him over. Joseph Stalin had become intrigued by reports of the Silbervogel design and sent his son, Vasily, and scientist Grigori Tokaty to kidnap Sänger and Bredt and bring them to the USSR.[4][5] When this plan failed, a new design bureau was set up by Mstislav Vsevolodovich Keldysh in 1946 to research the idea. A new version powered by ramjets instead of a rocket engine was developed, usually known as the Keldysh bomber, but not produced.[1] The design, however, formed the basis for a number of additional cruise missile designs right into the early 1960s, none of which were ever produced.

In the US, a similar project, the X-20 Dyna-Soar, was to be launched on a Titan II booster. As the manned space role moved to NASA and unmanned reconnaissance satellites were thought to be capable of all required missions, the United States Air Force gradually withdrew from manned space flight and Dyna-Soar was cancelled.

One lasting legacy of the Silverbird design is the "Regenerative cooling-regenerative engine" design, in which fuel or oxidizer is run in tubes around the engine bell in order to both cool the bell and pressurize the fluid. Almost all modern rocket engines use this design today and some sources still refer to it as the Sänger-Bredt design.

Sanger II Space Plane

On 18 October 1985 Messerschmidt-Boelkow-Bloehm (MBB) began renewed studies of the Saenger spaceplane, this time a "piggyback" two-stage-to-orbit horizontal takeoff concept.[6]

References

1.^ a b Westman, Juhani (2008-04-02). "Global Bounce". Retrieved 2010-04-27.

2.^ Reuter, C. The V2 and the German, Russian and American Rocket Program. CA: German Canadian Museum. pp. 96–97. ISBN 9781894643054.

3.^ Eugen Sänger; Irene Sänger-Bredt (August 1944) (PDF). A Rocket Drive For Long Range Bombers. Astronautix.com. Retrieved 2010-4-27.

4.^ Duffy, James P (2004). Target: America — Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States. Praeger. pp. 124. ISBN 0-275-96684-4.

5.^ Shayler, David J (2005). Women in Space — Following Valentina. Springer Verlag. pp. 119. ISBN 1-85233-744-3.

6.^ Sæger II, Astronautix.

From century-of-flight.net:

Nazi Germany’s Space Bomber

By:

Mr. R. Colon

rcolonfrias@yahoo.com

PO Box 29754

Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico 00929

When Germany unveiled its Sanger II space ship, a low-orbit, two stage shuttle vehicle capable of taking off and landing on conventional runways, at the 1986 Farnborough Air Show; it was a tribute to the work of the late German engineer Dr. Eugen Albert Sanger and his pioneering research in Germany into ram jet engines and advance rocketry. Work that provided the basis to one of the most advanced designs ever: the Space Bomber. Sanger was born in Bohemia in 1905. Since his early years, Sanger was fascinated by the words of Hermann Oberth, a famous space exploration writer. Oberth envisioned humans reaching low earth orbit utilizing a multi-stage missile system. It would be Oberth’s book, Rocket to the Planets, first published in 1923, that would lead Sanger to this strange new and developing field: rocketry. Sanger assimilated Oberth’s ideas and went further. He believed early on that if humans were to explore the universe, they did not necessarily need a multistage rocket to reach orbit, he championed the idea of using what he called an “stratospheric aircraft” to reach earth low orbit. In the summer of 1933, Sanger published a book titled Rocket Flight Technique in which he detailed his ideas for the development of an orbiting, manned space station.

The feedback from the still-infant aerospace community in Germany and the rest of the world was impressive. The success of Rocket lead Sanger to write, between 1934 and 1936, several major papers for the influential aviation magazine Flug, an Austrian publication well regarded in the aviation community. These papers caught the eyes of Luftwaffe officials who immediately realized the potential of rocket engines in the development of advance fighters and bombers. He was recruited in the fall of 1936 to work at the Hermann Goring Institute. There, Sanger was assigned the task of developing functional ram jet engines for fighters. He focused his attention on the development of an air-breathing engine. He started his research gathering all the information he could from a 1905 patent filed by French aviation pioneer Rene Lorin. Lorin’s original research data proved that air compressed inside an aluminium tube and expanded by a combustion reaction would generate an enormous amount of thrust.

By November 1941, Sanger’s team was producing concrete results. In one experiment, he mounted a sewer pipe atop an Opel truck. The truck was driven at 55mph, forcing air into the pipe, at the same time; gasoline was injected into the centre of the pipe and ignited. The result was nothing short of spectacular. The combustion was successfully maintained as long as the truck keep going at the same speed and the gasoline kept igniting. The results were so successful, that Sanger’s team commenced the development of an operational ram jet the following spring. In mid 1942, a newly design ram jet was fitted in the top of the fuselage of a Dornier 217E bomber. The engine performed flawlessly. It sustained its thrust as long as the fuel lasted. In fact, the experiment would have been even more impressive if the aircraft selected, the above mentioned Dornier 217E, could had handled the speeds the engine was capable of. The ram jet engine installed on this particular sample 217E was capable of speeds around 600mph while the aircraft’s fuselage could only sustain pressures at speeds of 350mph.

While performing his duties to the Luftwaffe, Sanger never lost track of his ultimate goal. The development of an aircraft capable of reaching low orbit. By early 1944, Sanger must have been aware of the ultra secret work being performed on Germany’s planned long range bomber, the A9 or America Bomber. Originally conceived in 1929; the Sanger concept of a bomber calling for a winged rocket design. He performed calculations on the design and, along with his wife, mathematician Irene Bredt; came up with the idea of an atmosphere re-entry platform. This vehicle would offer high payload and almost unlimited range since the aircraft would be “flying” in space, using small fuel cells, the low earth orbit and gravity would act as the aircraft’s main propulsion system. He proceeded to write a report titled On a rocket Propulsion Engine for Long Distance Bombers, in an attempt to gain government financial support for the development, and eventual production of what he called the Rocket Bomber. But by this time the tide of war had changed for Nazi Germany. Fighting for its survival, Nazi leaders needed weapon systems now, not another long term developing program. Sanger never got the financial resources he requested.

Nevertheless, Sanger and Bredt worked around the clock on his idea of a rocket bomber and in the spring of 1944, they produced a major paper on the benefits of his design, He distributed it to all the major players in Germany’s aerospace industry. Wernher von Braun, Werner Heisenberg, Dr. Ernst Heinkel, Willy Messerschmitt and Professor Dornier got copies of the paper. The paper explained in extraordinary detail, Sanger’s idea of a bomber capable of bombing cities in the United States from bases in Germany. He changed the name of the aircraft; it was now called the Silverbird Bomber. The Silverbird was designed to be a 100-ton monster, of the 100 tons, 90 would be use to store fuel.

The bomber would have been launched into the air by a sled fitted with a rocket engine capable of producing 610 tons of thrust for eleven violent seconds. After which the plane would be propelled to around 5,500ft in the air. Once airborne, the bomber power plant would ignite and the aircraft would climb steadily to an altitude of 130,000ft, slightly above the twenty five mile level of the denser atmosphere. It would then proceed to dive into thicker air where its wings would make the bomber ricochet back into a long and steep climb. This “ricochet” along with the remainder of the bomber’s fuel, would enable the aircraft to reach attitudes of around 160 to 175 miles above the earth surface. The bomber would then maintain its heading until it reaches its main target. The Silverbird would continued its flight until it reached Japanese controlled South Western Asia where it would deploy its tricycle undercarriage to perform the landing manoeuvre.

The German government was so impressed with the report, that it deemed it a State Secret. It was labelled with instructions intended to forbid copying or photographic it. It was placed in a steel safe and guarded twenty four-seven. When Germany collapsed in May 1945, Sanger and his wife, as well as many top ram jet engine engineers, went to work for the French Air Ministry.

In 1952, ‘Rocket’ was translated into English and became widely circulated among the Western Democracies’ air force research facilities. In the summer of 1954, Sanger and Bredt returned to Germany. They immediately began working for the West Germany government in the research of aircraft propulsion systems. Over the years, historians and pundits had given many different names to the Silverbird Bomber. Names such as the Orbital Bomber or the Atmosphere Skipper to name a few, were used to describe Sanger’s aircraft concept. But maybe the name that more resonates with the public is that of the Antipolar Bomber. Numerous articles and televisions documentaries have described the concept as the Antipolar Bomber.

As impressive as the Silverbird concept was, it never went beyond the design stages. Several test mock-ups were built and tested in wind tunnels during the 1950s, but with advances in conventional jet engines, mainly fuel consumption, the designs mock-ups never made it to the drawing board. But the idea never went fully away. Today, the United States utilize Sanger’s concepts in its impressive Shuttle Re-entry Vehicle.

References

Top Secret Tales of World War II, New York, John Wiley & Sons 2000

German Secret Weapons: Blueprint for Mars, New York, Ballantine Books 1969

German Heavy Bombers, Atglen PA, Schiffer Publishing Ltd 1994

From Luft '46:

In June 1935 and February 1936, Dr. Eugen Sänger published articles in the Austrian aviation publication Flug on rocket-powered aircraft. This led to his being asked by the German High Command to build a secret aerospace research institute in Trauen to research and build his "Silverbird", a manned, winged vehicle that could reach orbit. Dr. Sänger had been working on this concept for several years, and in fact he had began developing liquid-fuel rocket engines. From 1930 to 1935, he had perfected (through countless static tests) a 'regeneratively cooled' liquid-fueled rocket engine that was cooled by its own fuel, which circulated around the combustion chamber. This engine produced an astounding 3048 meters/second (10000 feet/second) exhaust velocity, as compared to the later V-2 rocket's 2000 meters/second (6560 feet/second). Dr. Sänger, along with his staff, continued work at Trauen on the "Silverbird" under the Amerika Bomber program.

In June 1935 and February 1936, Dr. Eugen Sänger published articles in the Austrian aviation publication Flug on rocket-powered aircraft. This led to his being asked by the German High Command to build a secret aerospace research institute in Trauen to research and build his "Silverbird", a manned, winged vehicle that could reach orbit. Dr. Sänger had been working on this concept for several years, and in fact he had began developing liquid-fuel rocket engines. From 1930 to 1935, he had perfected (through countless static tests) a 'regeneratively cooled' liquid-fueled rocket engine that was cooled by its own fuel, which circulated around the combustion chamber. This engine produced an astounding 3048 meters/second (10000 feet/second) exhaust velocity, as compared to the later V-2 rocket's 2000 meters/second (6560 feet/second). Dr. Sänger, along with his staff, continued work at Trauen on the "Silverbird" under the Amerika Bomber program. The Sänger Amerika Bomber (or Orbital Bomber, Antipodal Bomber or Atmosphere Skipper) was designed for supersonic, stratospheric flight (please see diagram below). The fuselage was flattened, which helped create lift and the wings were short and wedge shaped. There was a horizontal tail surface located at the extreme aft end of the fuselage, which had a small fin on each end. The fuel was carried in two large tanks, one on each side of the fuselage, running from the wings aft. Oxygen tanks were located one on each side of the fuselage, located forward of the wings. There was a huge rocket engine of 100 tons thrust mounted in the fuselage rear, and was flanked by two auxiliary rocket engines. The pilot sat in a pressurized cockpit in the forward fuselage, and a tricycle undercarriage was fitted for a gliding landing. A central bomb bay held one 3629 kg (8000 lb) free-falling bomb, and no defensive armament was fitted. The empty weight was to be approximately 9979 kg (22000 lbs).

An interesting flight profile was envisioned for the "Silverbird". It was to be propelled down a 3 km (1.9 mile) long monorail track by a rocket-powered sled that developed a 600 ton thrust for 11 seconds (please see diagram below). After taking off at a 30 degree angle and reaching an altitude of 1.5 km (5100'), a speed of 1850 km/h (1149 mph) would be reached. At this point, the main rocket engine would be fired for 8 minutes and burn 90 tons of fuel to propel the "Silverbird" to a maximum speed of 22100 km/h (13724 mph) and an altitude of over 145 km (90 miles), although some sources list the maximum altitude reached as 280 km (174 miles). As the aircraft accelerated and descended under the pull of gravity, it would then hit the denser air at about 40 km (25 miles) and 'skip' back up as a stone does when skipped along water (please see drawing below). This also had the added benefit of cooling the aircraft after the intense frictional heating encountered when the denser air was reached. The skips would gradually be decreased until the aircraft would glide back to a normal landing using its conventional tricycle landing gear, after covering approximately 23500 km (14594 miles).

The final test facilities for full-scale rocket engine tests were being built when Russia was invaded in June 1941. All futuristic programs were canceled due to the need to concentrate on proven designs. Dr. Sänger went on to work on ramjet designs for the DFS (German Research Institute for Gliding), and helped to design the Skoda-Kauba Sk P.14. Although the Luftwaffe did its best to stop Dr. Sänger from publishing his research results, a few copies went unaccounted for and made their way to other countries. After the war, he was asked to work (along with mathematician Irene Bredt) for the French Air Ministry, where in a bizarre plot, he was almost kidnapped by Stalin, who recognized the value of the Amerika Bomber.

![[silverbird-big.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhprYPzArguNV1PHPI0WVCUbyvF4oJEqIeuptZEKiJiSc-78auEMn84HhpIAJLXpS2Tl2R3lStcqHiZ2EQ15-lJO2fgAMGuQowmdfBXYl4JVIC_pgYg_WswF02R5SBl1J20Xggvep3gI9c/s640/silverbird-big.jpg)

From Wikipedia:

Amerika Bomber

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Amerika Bomber project was an initiative of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium, the Nazi Germany Air Ministry, to obtain a long-range strategic bomber for the Luftwaffe that would be capable of striking the continental United States from Germany, a range of about 5,800 km (c.3,600 mi.). Though the concept was raised as early as 1938, plans were not submitted to Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring until 1942. Various proposals were put forward, including using it to deliver an atomic bomb, but they were all eventually abandoned as too expensive.

Background

According to Spandau: The Secret Diaries, Hitler was fascinated with the idea of New York City in flames. In 1937, Willy Messerschmitt hoped to win a lucrative contract by showing Hitler a prototype of the Messerschmitt Me 264 that was being designed to reach North America from Europe.[1] On July 8, 1938, barely two years after the death of Germany's main strategic bombing advocate, Generalleutnant Walter Wever, the Luftwaffe's commander-in-chief Hermann Göring, gave a speech saying, "I completely lack the bombers capable of round-trip flights to New York with a 4.5-tonne bomb load. I would be extremely happy to possess such a bomber which would at last stuff the mouth of arrogance across the sea."[2] Canadian historian Holger H. Herwig[3] claims the plan started as a result of discussions by Hitler in November 1940 and May 1941 when he stated his need to “deploy long-range bombers against American cities from the Azores.” Due to their location, he thought the Portuguese Azores islands were Germany's “only possibility of carrying out aerial attacks from a land base against the United States.”[2] At the time, Portuguese dictator Salazar had allowed German U-boats and navy ships to refuel there, but from 1943 onwards, he leased bases in the Azores to the British, allowing the Allies to provide aerial coverage in the middle of the Atlantic.

Requests for designs, at various stages during the war, were made to the major German aircraft manufacturers (Messerschmitt, Junkers, Heinkel, Focke-Wulf and the Horten Brothers) early in World War II, coinciding with the passage of the Destroyers for Bases Agreement between the United States and the United Kingdom in September 1940.

The plan

The Amerika Bomber Project plan was completed on April 27, 1942 and submitted to Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring on May 12, 1942. The 33 page long plan was discovered in Potsdam by Olaf Groehler, a German historian. Ten copies of the plan were made, with six going to different Luftwaffe offices and four held in reserve. The plan specifically mentions using the Azores as a transit airfield to reach the United States. If utilized, the Heinkel He 277, Junkers Ju 290, and the Messerschmitt Me 264 could reach American targets with a 3 ton, 5 ton, and 6.5 ton payload respectively.[2] Although it is apparent that the plan itself deals only with an attack on American soil, it is possible the Nazis saw other, interrelated strategic purposes for the Amerika Bomber project. According to military historian James P. Duffy, Hitler "saw in the Azores the ... possibility for carrying out aerial attacks from a land base against the United States ... [which in turn would] force it to build up a large antiaircraft defense."[2] The anticipated result would have been to force the United States to use more of its antiaircraft capabilities - i.e. guns and fighter planes - for its own defense rather than for that of Great Britain, thereby allowing the Luftwaffe to attack the latter country with less resistance.

Potential targets

Included in the plan was a list of 21 targets of military importance. Of these, 19 were located in the United States and the remaining two in Vancouver, Canada and the southern tip of Greenland. Nearly all were companies that manufactured parts for aircraft, so the goal for Nazis was likely to cripple American production of aircraft. The 19 targets are listed below by company and location.[2]

Aluminum Corp. of America in Alcoa, Tennessee

Aluminum Corp. of America in Massena, New York

Aluminum Corp. of America in Badin, North Carolina

Wright Aeronautical Corp. in Paterson, New Jersey

Pratt & Whitney Aircraft in East Hartford, Connecticut

Allison Division of G.M. in Indianapolis, Indiana

Wright Aeronautical Corp. in Cincinnati, Ohio

Hamilton Standard Corp. in E. Hartford, Connecticut

Hamilton Standard Corp. in Pawcatuck, Connecticut

Curtiss Wright Corp. in Beaver, Pennsylvania

Curtiss Wright Corp. in Caldwell, New Jersey

Sperry Gyroscope in Brooklyn, New York

Cryolite Refinery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

American Car & Foundry in Berwick, Pennsylvania

Colt Manufacturing in Hartford, Connecticut

Chrysler Corp. in Detroit, Michigan

Allis-Chalmers in La Porte, Indiana

Corning Glass Works in Corning, New York

Bausch & Lomb in Rochester, New York

Conventional bombers

The most promising proposals were based on conventional principles of aircraft design and would have yielded aircraft very similar in configuration and capability to the Allied heavy bombers of the day. These included the Messerschmitt Me 264 (an all-new design), the Focke-Wulf Fw 300 (based on the existing Fw 200), Focke Wulf Ta 400, and the Junkers Ju 390 (based on the Ju 290), as well as the Heinkel He 277, which from its design's ongoing development through 1943, eventually ended up as worthy to compete for the "Amerika Bomber" role. Prototypes of the Me 264 were built, but it was the Ju 390 that was selected for production. Only three prototypes each, of both the Me 264 and Ju 390 designs, were constructed before the programmes were abandoned. It has been claimed[citation needed] in a number of postwar World War II air combat subject books, that in early 1944 the second prototype of the Ju 390 made a trans-Atlantic flight to within 20 km (12 mi) of the northeast U.S. coast.

Huckepack Projekt (Piggyback Project)

One idea similar to Mistel-Gespann was to have a Heinkel He 177 bomber carry a Dornier Do 217, powered with an additional Lorin-Staustrahltriebwerk (Lorin-ramjet), as far as possible over the Atlantic before releasing it. For the Do-217 it would have been a one-way trip. The plane would be ditched off the east coast, and its crew would be picked up by a U-boat that was waiting nearby. When plans had advanced far enough, the lack of fuel and the loss of the base at Bordeaux prevented a test. The project was abandoned after the forced move to Istres increased the distance too much.

Atomic bomber

The controversial revisionist British historian David Irving stated that a method of bombing New York City was discussed at several Luftwaffe conferences in May and June 1942. One idea that received a lot of attention was the Huckepack Projekt (piggyback project). Initially Field-Marshal Erhard Milch vetoed the plan due to the small payload that would be delivered for such a massive project. However, on June 4, 1942, Erhard Milch and Albert Speer attended a lecture by Werner Heisenberg on atomic fission at the Harnack-Haus.[4] After the lecture, Speer asked Heisenberg if this research could design an atom bomb. Heisenberg replied that it could be done, but would take as long as two years. Speer then asked how large a bomb would need to be to destroy a city to which Heisenberg replied the size of a football.[2] Heisenberg requested funds, rare materials, and scientists be released from the army to continue their research. The Huckepack Projekt was brought up again at multiple joint conferences between the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. However, after a few weeks the plan was abandoned on August 21, 1942. Air Staff General Kreipe wrote in his diary that the German Navy could not supply a U-boat offshore of the United States to pick up the aircrew. The plan saw no further development, since the Kriegsmarine would not cooperate with the Luftwaffe.[2]

Flying wings

Other proposals were far more exotic jet- and rocket-powered designs, e.g. as a flying wing. The Horten brothers designed the Horten Ho XVIII,[5] a flying wing powered by six turbojets based on experiences with their existing Ho X design. The Arado company also suggested a six-jet flying wing design, the Arado E.555.[6]

Daimler-Benz Project C

Another proposal was the Daimler-Benz Project C. This was a huge carrier aircraft, carrying either five "Project E" aircraft or six "Project F" aircraft. The smaller aircraft had jet-engines and were designed to be kamikaze-airplanes.[7][8][9]

Winged rockets

Wind tunnel model of Eugen Sänger's Silbervogel

Other designs were rockets with wings. Perhaps the best-known of these today is Eugen Sänger's pre-war Silbervogel ("Silverbird") sub-orbital bomber. While the A4b rocket, winged version of the V-2 rocket and probably its successor A9 rocket were tested several times in late 1944/early 1945, the A9/A10 Amerika-Rakete, planned as a full 2-staged ICBM, remained a project.[10]

Feasibility

All of these projects were deemed too expensive and ambitious and were abandoned, although the British Air Ministry considered development of the Ho XVIII for an airliner after the war[citation needed], and the theoretical groundwork done on the Silbervogel would prove seminal to lifting body designs of the space age.

According to British Intelligence, a German prisoner of war was quoted saying that since the beginning of 1944, “…regular air travel between Germany and Japan established for the transport of high officials,” took place with the Messerschmitt Me 264.[11] The distance from Frankfurt, Germany to Tokyo, Japan is 9,160 km (5,691 mi) whereas the distance from New York City, New York to Paris, France is 5,840 km (3,628 mi) to put this in perspective. Although in the case of bombing New York City, that distance must be doubled to 11,680 km (7,256 mi) as the bomber will not be able to land as it did in Tokyo. The only German World War II aircraft built that had anything close to this specified range was the Messerschmitt Me 261 Adolfine, with a maximum range of 11,025 km (6,850 mi). Many engineering challenges would have to have been overcome for the bomber to be an effective weapon. Had Hitler spent more time and resources on this project, it may have had a chance of working. However, unless Germany developed an atomic bomb, which would have taken even more time and resources, it is unlikely this aircraft would have made a big impact on the outcome of the war.

Why the plan failed

Duffy believed that Nazi Germany had no central authority over the development and construction of advanced weaponry. Because of this, German scientists were forced to compete for resources that were already scarce due to the war. Hitler was often swayed to spend more time, money and resources on his “miracle weapons” or projects that were exciting and new, but less likely to be successful. As a result insufficient attention was given to the Amerika Bomber project. The project failed to come to fruition, not because the transatlantic bomber was not feasible, but because the Nazis were unable to manufacture enough parts to produce the aircraft. The Allied bombing was so intense near the end of the war it disrupted the German supply chain. Also, the German war machine was running very low on supplies, particularly fuel and kept what little was left for defense.[2]

References

1.^ Elke Frenzel Hitler's Unfulfilled Dream of a New York in Flames Der Spiegel 16 September 2010

2.^ a b c d e f g h Duffy, James P. Target America: "Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States". The Lyons Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1-59228-934-9.

3.^ http://hist.ucalgary.ca/faculty/herwig-holger-h

4.^ Rose, Paul; Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi atomic bomb project: a study in German culture By Paul Lawrence Rose Heisenberg and the Nazi atomic bomb project. ISBN 978-0-520-22926-6.

5.^ Horten XVIII, luft46.

6.^ Arado 555, luft46.

7.^ Project C, WW2 in color.

8.^ Project C, Above Top Secret

9.^ (GIFF) Project D, Something Awful.

10.^ http://www.luft46.com/misc/sanger.html Sänger page on luft46.com

11.^ Me 264 Forsyth, Robert. Messerschmitt Me 264 America Bomber: The Luftwaffe’s Lost Transatlantic Bomber. Ian Allen Publishing, 2006 ISBN 1-903223-65-2.

Further reading

Luftfahrt History Heft 4 - Messerschmitt Me 264 & Junkers Ju 390 *Atomziel New York - Geheime Großraketen- und Raumfahrtprojekte des Dritten Reichs

Griehl, Manfred and Dressel, Joachim. Heinkel He 177-277-274, Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury, England 1998. ISBN 1-85310-364-0.

Green, William. Warplanes of the Third Reich. London: Macdonald and Jane's Publishers Ltd., 1970. ISBN 0-356-02382-6.

Herwig, Dieter and Rode, Heinz. Luftwaffe Secret Projects - Strategic Bombers 1935-45. Midland Publishing Ltd., 2000. ISBN 1-85780-092-3.

Smith, J.R. and Kay, Anthony. German Aircraft of the Second World War. London: Putnam and Company, Ltd., 1972. ISBN 0-370-00024-2.

Duffy, James P. Target America: Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States. The Lyons Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1-59228-934-9.

Eugen Sänger

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Eugen Sänger

Born: 22 September 1905, Preßnitz

Died: 10 February 1964

Nationality: German

Work

Significant advance: lifting body and ramjet

Eugen Sänger (22 September 1905 - 10 February 1964) was an Austrian-German aerospace engineer best known for his contributions to lifting body and ramjet technology.

Early career

Sänger was born in the former mining town of Preßnitz (Přísečnice), Chomutov (flooded by the Preßnitz dam in 1974) in Bohemia, at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He studied civil engineering at the Technical Universities of Graz and Vienna. As a student, he came in contact with Hermann Oberth's book Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen ("By Rocket into Planetary Space"), which inspired him to change from studying civil engineering to aeronautics. He also joined Germany's amateur rocket movement, the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (VfR - "Society for Space Travel") which was centered on Oberth.

Sänger made rocket-powered flight the subject of his thesis, but it was rejected by the university as too fanciful. He was allowed to graduate when he submitted a far more mundane paper on the statics of wing trusses. Sänger would later publish his rejected thesis under the title Raketenflugtechnik ("Rocket Flight Engineering") in 1933. In 1935 and 1936, he published articles on rocket-powered flight for the Austrian journal Flug ("Flying.") These attracted the attention of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM, or "Reich Aviation Ministry") which saw Sänger's ideas as a potential way to accomplish the goal of building a bomber that could strike the United States from Germany (the Amerika Bomber project).

Sub-orbital bomber concept

Main article: Silbervogel

Sänger agreed to lead a rocket development team in the Lüneburger Heide region in 1936. He gradually conceived a rocket-powered sled that would launch a bomber with its own rocket engines that would climb to the fringe of space and then skip along the upper atmosphere - not actually entering orbit, but able to cover vast distances in a series of sub-orbital hops. This remarkable design was called the Silbervogel ("Silverbird") and would have relied on its fuselage creating lift (as a lifting body) to carry it along its sub-orbital path. Sänger was assisted in this design by mathematician Irene Bredt, whom he married. Sänger also designed the rocket motors that the space-plane would use, which would need to generate 1 meganewton (225,000 lbf) of thrust. In this design, he was one of the first to suggest using the rocket's fuel as a way of cooling the engine, by circulating it around the rocket nozzle before burning it in the engine.

By 1942, the Reich Air Ministry canceled this project along with other more ambitious and theoretical designs in favour of concentrating on proven technologies. Sänger was sent to work for the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug (DFS, or "German Gliding Research Institute"). There he did important work on ramjet technology until the end of World War II.

Postwar

After the war ended, Sänger worked for the French government and in 1949 founded the Fédération Astronautique. Whilst in France, he was the subject of a botched attempt by Soviet agents to win him over. Joseph Stalin had become intrigued by reports of the Silbervogel design and sent his son, Vasily, and scientist Grigori Tokaty to convince him to come to the Soviet Union, but they failed to do so. It has also been reported that Stalin instructed the NKVD to kidnap him.[1]

In 1951, he became the first President of the International Astronautical Federation.

By 1954, Sänger had returned to Germany and three years later was directing a jet propulsion research institute in Stuttgart. Between 1961 and 1963 he acted as a consultant for Junkers in designing a ramjet-powered space-plane that never left the drawing board. Sänger's other theoretical innovations during this period were proposing means of using photons for interplanetary and interstellar spacecraft propulsion, including the solar sail.

He died in Berlin. The Sänger's grave is located on the cemetery "Alter Friedhof" in Stuttgart-Vaihingen. His work on the Silbervogel would prove important to the X-15, X-20 Dyna-Soar, and ultimately Space Shuttle programs.

Honours

Elected Honorary Fellow of the British Interplanetary Society (B.I.S.) in 1949[2]

Notes

1.^ Wade, Mark. "Keldysh Bomber". Astronautix.com. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

2.^ "Dr Eugen Sänger". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society March 1950 vol 9 No.2. 1950.

References

Books and technical reports

Sänger, Eugen (1956). Zur Mechanik der Photonen-Strahlantriebe. München,: R. Oldenbourg. pp. 92.

Sänger, Eugen (1957). Zur Stahlungsphysik der Photonen-Strahlantriebe und Waffenstrahlen. München: R. Oldenbourg. pp. 173.

Sänger, Eugen (1933). Rocket Flight Engineering. (Washington, 1965): NASA Tech. Trans. F-223.

Sänger, Eugen; Irene Sänger-Bredt (August 1944). "A Rocket Drive For Long Range Bombers" (PDF). Astronautix.com. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

Saenger, Hartmut E and Szames, Alexandre D, From the Silverbird to Interstellar Voyages, IAC-03-IAA.2.4.a.07.

Sänger, Eugen; trans, Karl Frucht (1965). Space Flight: Countdown for the Future. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Duffy, James P. (2004). TARGET: AMERICA : Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96684-4.

Shayler, David J. (2005). Women in Space - Following Valentina. Springer. ISBN 1-85233-744-3.

Other

Westman, Juhani (2006). "Global Bounce". Retrieved 2008-01-17.

Wade, Mark. "Eugen Albert Saenger". Astronautix.com. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

From Wikipedia:

Silbervogel

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Sänger Silbervogel wind tunnel model

Silbervogel, German for silver bird, was a design for a rocket-powered sub-orbital bomber aircraft produced by Eugen Sänger and Irene Bredt in the late 1930s for The Third Reich/Nazi Germany. It is also known as the RaBo (Raketenbomber or "rocket bomber"). It was one of a number of designs considered for the Amerika Bomber mission. When Walter Dornberger attempted to create interest in military spaceplanes in the United States after World War II, he chose the more diplomatic term antipodal bomber.

Concept

The design was a significant one, as it incorporated new rocket technology, and the principle of the lifting body, forshadowing future development of winged spacecraft such as the X-20 Dyna-Soar of the 1960s and the Space Shuttle of the 1970s. In the end, it was considered too complex and expensive to produce. The design never went beyond mock up test.

The Silbervogel was intended to fly long distances in a series of short hops. The aircraft was to have begun its mission propelled along a 3 km (2 mi) long rail track by a large rocket-powered sled to about 1,930 km/h (1,200 mph). Once airborne, it was to fire its own rocket engine and continue to climb to an altitude of 145 km (90 mi), at which point it would be travelling at some 22,100 km/h (13,700 mph). It would then gradually descend into the stratosphere, where the increasing air density would generate lift against the flat underside of the aircraft, eventually causing it to "bounce" and gain altitude again, where this pattern would be repeated. Because of drag, each bounce would be shallower than the preceding one, but it was still calculated that the Silbervogel would be able to cross the Atlantic, deliver a 4,000 kg (8,800 lb) bomb to the continental US, and then continue its flight to a landing site somewhere in the Japanese held Pacific, a total journey of 19,000 to 24,000 km (12,000 to 15,000 mi).

Postwar analysis of the Silbervogel design involving a mathematical control analysis unearthed a computational error and it turned out that the heat flow during the initial re-entry would have been far higher than originally calculated by Sänger and Bredt; if the Silbervogel had been constructed according to their flawed calculations the craft would have been destroyed during re-entry. The problem could have been solved by augmenting the heat shield, but this would have reduced the craft's already small payload capacity.[1]

History

On 3 December 1941 Sänger sent his initial proposal for a suborbital glider to the Reich Air Ministry (RLM) as Geheime Kommandosache Nr. 4268/LXXX5. The 900-page proposal was regarded with disfavor at the RLM due to its size and complexity and was filed away.

Professor Walter Gregorii had Sänger rework his report and a greatly reduced version was submitted to the RLM in September 1944, as UM 3538. It was the first serious proposal for a vehicle which could carry a pilot and payload to the lower edge of space.

Two manned and one unmanned version were proposed: the Antipodenferngleiter (antipodal long-range glider) and the Interglobalferngleiter (intercontinental long-range glider). Both were to be launched from a rocket-powered sled. The two manned versions were identical except in payload. The Antipodenferngleiter was to be launched at a very steep angle (which would shorten the range) and after dropping its bomb load on New York City was to land at a Japanese base in the Pacific.[2]

Postwar

After the war ended, Sänger and Bredt worked for the French government[3] and in 1949 founded the Fédération Astronautique. Whilst in France, Sänger was the subject of a botched attempt by Soviet agents to win him over. Joseph Stalin had become intrigued by reports of the Silbervogel design and sent his son, Vasily, and scientist Grigori Tokaty to kidnap Sänger and Bredt and bring them to the USSR.[4][5] When this plan failed, a new design bureau was set up by Mstislav Vsevolodovich Keldysh in 1946 to research the idea. A new version powered by ramjets instead of a rocket engine was developed, usually known as the Keldysh bomber, but not produced.[1] The design, however, formed the basis for a number of additional cruise missile designs right into the early 1960s, none of which were ever produced.

In the US, a similar project, the X-20 Dyna-Soar, was to be launched on a Titan II booster. As the manned space role moved to NASA and unmanned reconnaissance satellites were thought to be capable of all required missions, the United States Air Force gradually withdrew from manned space flight and Dyna-Soar was cancelled.

One lasting legacy of the Silverbird design is the "Regenerative cooling-regenerative engine" design, in which fuel or oxidizer is run in tubes around the engine bell in order to both cool the bell and pressurize the fluid. Almost all modern rocket engines use this design today and some sources still refer to it as the Sänger-Bredt design.

Sanger II Space Plane

On 18 October 1985 Messerschmidt-Boelkow-Bloehm (MBB) began renewed studies of the Saenger spaceplane, this time a "piggyback" two-stage-to-orbit horizontal takeoff concept.[6]

References

1.^ a b Westman, Juhani (2008-04-02). "Global Bounce". Retrieved 2010-04-27.

2.^ Reuter, C. The V2 and the German, Russian and American Rocket Program. CA: German Canadian Museum. pp. 96–97. ISBN 9781894643054.

3.^ Eugen Sänger; Irene Sänger-Bredt (August 1944) (PDF). A Rocket Drive For Long Range Bombers. Astronautix.com. Retrieved 2010-4-27.

4.^ Duffy, James P (2004). Target: America — Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States. Praeger. pp. 124. ISBN 0-275-96684-4.

5.^ Shayler, David J (2005). Women in Space — Following Valentina. Springer Verlag. pp. 119. ISBN 1-85233-744-3.

6.^ Sæger II, Astronautix.

From century-of-flight.net:

Nazi Germany’s Space Bomber

By:

Mr. R. Colon

rcolonfrias@yahoo.com

PO Box 29754

Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico 00929

When Germany unveiled its Sanger II space ship, a low-orbit, two stage shuttle vehicle capable of taking off and landing on conventional runways, at the 1986 Farnborough Air Show; it was a tribute to the work of the late German engineer Dr. Eugen Albert Sanger and his pioneering research in Germany into ram jet engines and advance rocketry. Work that provided the basis to one of the most advanced designs ever: the Space Bomber. Sanger was born in Bohemia in 1905. Since his early years, Sanger was fascinated by the words of Hermann Oberth, a famous space exploration writer. Oberth envisioned humans reaching low earth orbit utilizing a multi-stage missile system. It would be Oberth’s book, Rocket to the Planets, first published in 1923, that would lead Sanger to this strange new and developing field: rocketry. Sanger assimilated Oberth’s ideas and went further. He believed early on that if humans were to explore the universe, they did not necessarily need a multistage rocket to reach orbit, he championed the idea of using what he called an “stratospheric aircraft” to reach earth low orbit. In the summer of 1933, Sanger published a book titled Rocket Flight Technique in which he detailed his ideas for the development of an orbiting, manned space station.

The feedback from the still-infant aerospace community in Germany and the rest of the world was impressive. The success of Rocket lead Sanger to write, between 1934 and 1936, several major papers for the influential aviation magazine Flug, an Austrian publication well regarded in the aviation community. These papers caught the eyes of Luftwaffe officials who immediately realized the potential of rocket engines in the development of advance fighters and bombers. He was recruited in the fall of 1936 to work at the Hermann Goring Institute. There, Sanger was assigned the task of developing functional ram jet engines for fighters. He focused his attention on the development of an air-breathing engine. He started his research gathering all the information he could from a 1905 patent filed by French aviation pioneer Rene Lorin. Lorin’s original research data proved that air compressed inside an aluminium tube and expanded by a combustion reaction would generate an enormous amount of thrust.

By November 1941, Sanger’s team was producing concrete results. In one experiment, he mounted a sewer pipe atop an Opel truck. The truck was driven at 55mph, forcing air into the pipe, at the same time; gasoline was injected into the centre of the pipe and ignited. The result was nothing short of spectacular. The combustion was successfully maintained as long as the truck keep going at the same speed and the gasoline kept igniting. The results were so successful, that Sanger’s team commenced the development of an operational ram jet the following spring. In mid 1942, a newly design ram jet was fitted in the top of the fuselage of a Dornier 217E bomber. The engine performed flawlessly. It sustained its thrust as long as the fuel lasted. In fact, the experiment would have been even more impressive if the aircraft selected, the above mentioned Dornier 217E, could had handled the speeds the engine was capable of. The ram jet engine installed on this particular sample 217E was capable of speeds around 600mph while the aircraft’s fuselage could only sustain pressures at speeds of 350mph.

While performing his duties to the Luftwaffe, Sanger never lost track of his ultimate goal. The development of an aircraft capable of reaching low orbit. By early 1944, Sanger must have been aware of the ultra secret work being performed on Germany’s planned long range bomber, the A9 or America Bomber. Originally conceived in 1929; the Sanger concept of a bomber calling for a winged rocket design. He performed calculations on the design and, along with his wife, mathematician Irene Bredt; came up with the idea of an atmosphere re-entry platform. This vehicle would offer high payload and almost unlimited range since the aircraft would be “flying” in space, using small fuel cells, the low earth orbit and gravity would act as the aircraft’s main propulsion system. He proceeded to write a report titled On a rocket Propulsion Engine for Long Distance Bombers, in an attempt to gain government financial support for the development, and eventual production of what he called the Rocket Bomber. But by this time the tide of war had changed for Nazi Germany. Fighting for its survival, Nazi leaders needed weapon systems now, not another long term developing program. Sanger never got the financial resources he requested.

Nevertheless, Sanger and Bredt worked around the clock on his idea of a rocket bomber and in the spring of 1944, they produced a major paper on the benefits of his design, He distributed it to all the major players in Germany’s aerospace industry. Wernher von Braun, Werner Heisenberg, Dr. Ernst Heinkel, Willy Messerschmitt and Professor Dornier got copies of the paper. The paper explained in extraordinary detail, Sanger’s idea of a bomber capable of bombing cities in the United States from bases in Germany. He changed the name of the aircraft; it was now called the Silverbird Bomber. The Silverbird was designed to be a 100-ton monster, of the 100 tons, 90 would be use to store fuel.

The bomber would have been launched into the air by a sled fitted with a rocket engine capable of producing 610 tons of thrust for eleven violent seconds. After which the plane would be propelled to around 5,500ft in the air. Once airborne, the bomber power plant would ignite and the aircraft would climb steadily to an altitude of 130,000ft, slightly above the twenty five mile level of the denser atmosphere. It would then proceed to dive into thicker air where its wings would make the bomber ricochet back into a long and steep climb. This “ricochet” along with the remainder of the bomber’s fuel, would enable the aircraft to reach attitudes of around 160 to 175 miles above the earth surface. The bomber would then maintain its heading until it reaches its main target. The Silverbird would continued its flight until it reached Japanese controlled South Western Asia where it would deploy its tricycle undercarriage to perform the landing manoeuvre.

The German government was so impressed with the report, that it deemed it a State Secret. It was labelled with instructions intended to forbid copying or photographic it. It was placed in a steel safe and guarded twenty four-seven. When Germany collapsed in May 1945, Sanger and his wife, as well as many top ram jet engine engineers, went to work for the French Air Ministry.

In 1952, ‘Rocket’ was translated into English and became widely circulated among the Western Democracies’ air force research facilities. In the summer of 1954, Sanger and Bredt returned to Germany. They immediately began working for the West Germany government in the research of aircraft propulsion systems. Over the years, historians and pundits had given many different names to the Silverbird Bomber. Names such as the Orbital Bomber or the Atmosphere Skipper to name a few, were used to describe Sanger’s aircraft concept. But maybe the name that more resonates with the public is that of the Antipolar Bomber. Numerous articles and televisions documentaries have described the concept as the Antipolar Bomber.

As impressive as the Silverbird concept was, it never went beyond the design stages. Several test mock-ups were built and tested in wind tunnels during the 1950s, but with advances in conventional jet engines, mainly fuel consumption, the designs mock-ups never made it to the drawing board. But the idea never went fully away. Today, the United States utilize Sanger’s concepts in its impressive Shuttle Re-entry Vehicle.

References

Top Secret Tales of World War II, New York, John Wiley & Sons 2000

German Secret Weapons: Blueprint for Mars, New York, Ballantine Books 1969

German Heavy Bombers, Atglen PA, Schiffer Publishing Ltd 1994

No comments:

Post a Comment